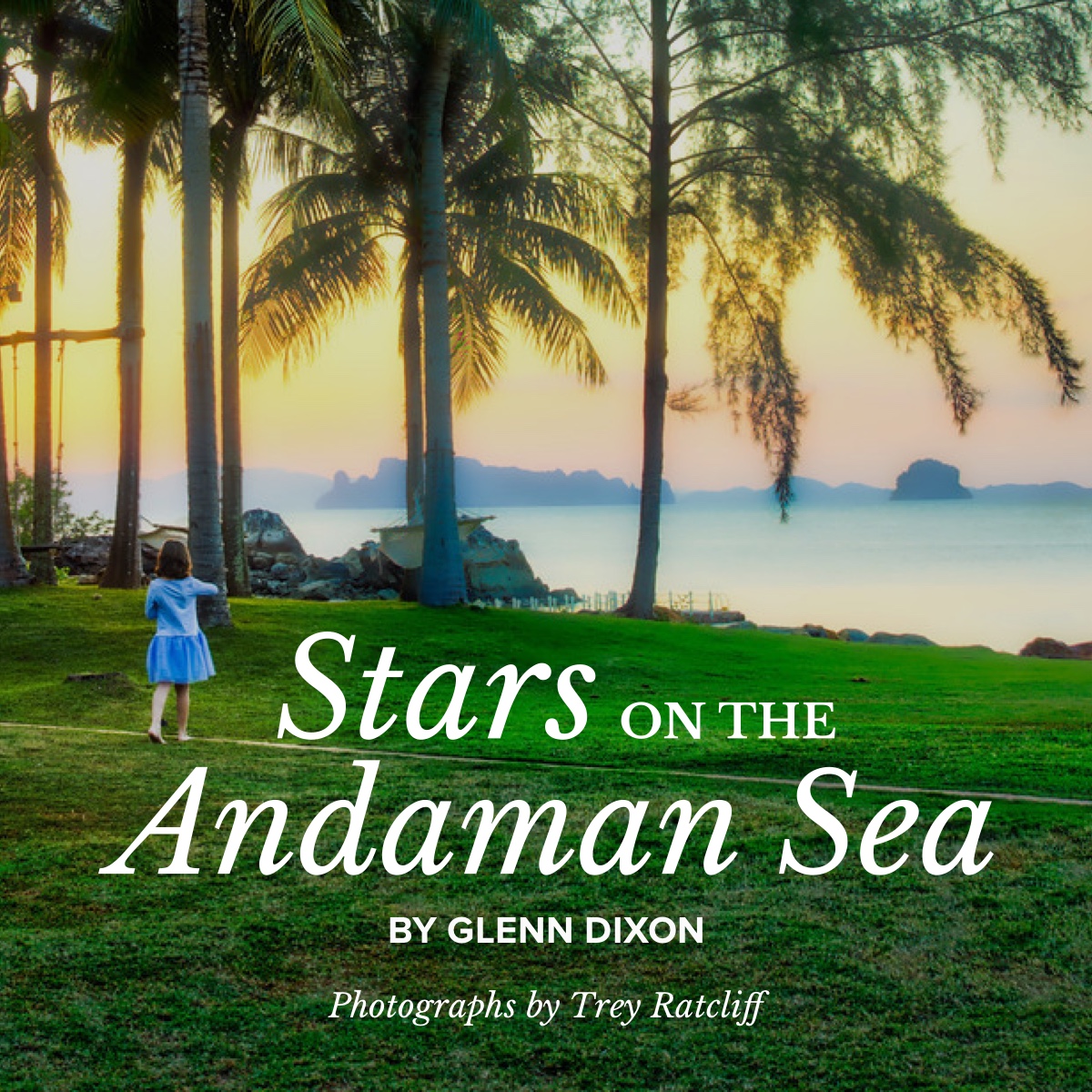

This short story was inspired by Trey Ratcliff's photographs, part of his "80 Stays Around the World" collaboration with The Ritz-Carlton and taken at Phulay Bay, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve, and near The Ritz-Carlton New York, Central Park.

Ariadne’s toes left tiny indentations in the wet sand. She watched the seafoam pearl over them and she skittered back a step, just out of reach of the water. Her father stood behind her. He smelled of shaving cream and sunscreen.

“Go on in, Ariadne,” he said. “It won’t hurt you.”

“It’s cold.”

“The water isn’t cold here. Go on. Give it a try.” Her father wore red swimming trunks, something she’d never seen him wear before. His legs were strong and already bronzed by the sun and she knew that he was at least a little bit famous. He lifted her up, cupping his hands under her armpits, her feet dangling.

“Daddy!”

“Just put your feet in.”

He set her down and a wave came in, splashing over her knees. “Oh,” she said. The push of the water was gentle and it was almost as warm as bathwater. Her father stood behind her and the ocean was an emerald-green. Out in the bay, rocky islands sprouted from the water and she thought they looked like the foreheads of sea giants peeking above the surface.

“See?” he said.

Or maybe they could be the homes of mermaids. Ariadne’s feet beneath the water were white and small. She wiggled her toes and the sand wafted up like smoke from a chimney. Then another wave splashed up against her legs and she stepped back into her father’s arms.

“Ten more minutes,” he said. “Then I have to go.”

He had shown her the place on a map. “Is it China?” Ariadne asked.

“No.” Her father stifled a grin. “It’s down from there. It’s Thailand. See, it’s here near the Bay of Bengal. We’re going to be on the Andaman Sea.” He slid a finger down the blue ocean between India and the long peninsula dripping down from Southeast Asia.

“Will there be tigers?”

“Maybe.”

“Is it beautiful?” she asked.

“It is. It’s tropical and warm, and…” He stopped. She was fidgeting, tracing her finger absently on the map.

“Are you making another movie there?” she said.

“Yes, honey. I write the script, the words, and then the actors…”

“I know how they make movies, Daddy. You don’t have to tell me.”

“Okay, okay.” He put his hand under her chin. “It’s a long ways away.

She was squirming in her chair now.

“Should we go for a walk?” he said.

“Okay.”

“Are you sad, honey?”

“I miss her.”

“I know, I miss her too. Come, let’s go to the park.”

She put on her pink rubber boots by the door and they rode the elevator down. He held her hand and she listened as they clunked down the six floors to go outside. The sky was clear but the blue was already thickening into twilight. Lights were popping on in the office building across the street and Ariadne took in its mirrored façade, the way it reflected their own apartment building, cutting it into cubes, distorting it like puzzle pieces. The park was only a couple of blocks east, and the sidewalks were wide and free though the street was full of cars, almost at a standstill in the rush hour traffic. A bicycle courier swept by them, swerving between the cars and her father took her hand while she clumped along in her boots. They crossed at 59th Street, past the statue of the man on a horse and on down the path into the woods. She always thought the statue marked the edge of the world, a quiet forest ahead of them, the city behind them.

Autumn had come to the park. The old cast iron lamp posts had popped on and the ground was blanketed with curled yellow leaves. She thought it looked like Narnia.

“Daddy,” she asked, without looking up at him. “Do you think it’s magic here?”

“I don’t think magic is real, honey. It’s pretty though, isn’t it?”

“Will we live here forever?”

“Maybe. New York is a good place for me. For my work.”

“You can make movies?”

“I write the scripts, honey. Other people make the movies.”

“Yes, but you make the words.”

“I do.” He squeezed her tiny hand. “I make the words.”

“And that’s the most important job, right?”

“I suppose so, honey.

She looked up. “I can’t see any stars.”

He looked up too. “There are too many lights in this city.”

“That’s crazy,” she said. “The stars are bigger than anything.”

“That’s true, but they’re very far away.”

“Like Thailand,” she said.

Ariadne plodded up the pathway from the beach, leaving wet footprints behind her. The pavement was still warm and a striped towel was wrapped around her shoulders and pulled up over her head like a cowl. Her father strode ahead of her, trying to hurry her but she slowed until the distance between them was enough that he’d notice. He stopped and turned.

“Honey?” he said. “I’m going to be late.”

She was staring up. “The trees look like umbrellas,” she said.

“Palm trees, honey.”

“They don’t grow in New York?”

“No, honey. They’re tropical. I told you already.” He took two steps back to her and knelt down, tugging the towel a little tighter over her forehead. He studied the tiny eyes staring out at him. He waited for her to speak.

“Will Mommy be happy?”

“I think so, yes.” He expected tears now, but she wrinkled her nose in thought.

“She must be very far away.”

“Something like that.”

“She’s as far away as the stars,” reasoned Ariadne, “but I think she can still see me. She can watch out for me.”

“She loved you very, very much, Ariadne. We all do.”

He lifted her chin with a single finger. “But I’m here, Ariadne. I’m going to look after you.”

“Forever?”

“Forever and ever. I promise.”

“I think they’re funny.”

“What are, honey?”

“The umbrella trees. We can stand under them when it rains.” He took her hand and they walked again, up into the hotel grounds. Her father, she thought, looked even more handsome than the movie stars he worked with. He was the smart one. He wrote every single word that they said.

Her favorite part of the path was the wooden bridge. She liked the hollow thump it made when she stomped on it, especially with her shoes. At night, the trees around it were wrapped with tiny blue sparkling lights.

“You’re going to be brave, right?” he said as they walked. “We’ll get you dressed and I’ll drop you at the kids’ centre.”

“I don’t like other kids.”

“How do you know? You haven’t met them yet.”

“I want to be with you.”

“I have to go to work, honey. You know that. I’ll just be a few hours.”

Ariadne sat at a green plastic table in a blue periwinkle dress. There were two other kids, a brother and a sister, but they were playing by themselves with some plastic fish. Sitting with her at the table was a lady, the teacher, who sat on a plastic chair much too small for her. Ariadne liked her for that. She liked that the woman didn’t have to pretend she was an adult.

“Do you like to draw?” the woman was saying. “I can get you some paper, and some crayons.”

Ariadne rose and followed her to a cupboard. The woman’s hair was long and black and tied in a ponytail. It was so black that it shone. She wore a light blue suit though, almost like pajamas and a cloth belt around it, like a karate uniform. “What’s your name?” asked Ariadne.

“My name is Malee,” the woman said.

“What’s that?”

“It’s Thai. It means flower.”

“My name is Ariadne. It’s the name of a princess, from a story, an old story. I think it’s not true.”

“It’s a very pretty name.”

“And I can speak two and a half languages,” said Ariadne.

“Yes?”

“My mother was Spanish but my father is only half Greek.”

“Do you speak Spanish?”

“Es fácil hablar español,” she said. “Can I draw a mermaid?”

“That’s a good idea. Choose a color.”

“Can I take two colors?”

“You can take as many as you like.”

Ariadne returned to the table with a fist full of crayons. She sat and squared the paper in front of her, finally pressing a deep purple crayon to the paper, furrowing her brow in concentration.

Malee walked her out to meet her father. They walked side by side along the path and came to an old man with a bucket. He wore jeans, even in the heat, and great rubber boots, and a floppy hat to protect him from the sun.

“Sawat Dee Khrap,” he said to the both of them. He had dirt on the knees of his jeans.

“Sawat Dee Kha,” said Malee. She pressed the palms of her hands together like a prayer and nodded at the man.

“This is Ariadne,” said Malee and the man turned to her. His face was wrinkled with age but he smiled and his eyes crinkled a bit.

“I don’t know your words,” said Ariadne.

Malee laughed and it was like wind chimes. “This is Preecha. He is the head groundskeeper. He knows everything about the plants here.”

“Yes, but what did he say?”

The man spoke then, his voice a gentle sing song. “Sawat Dee Khrap, it means hello, but only for boys.”

“That’s right,” said Malee. “Girls will say Kha.”

“The girls have their own language?” Ariadne stopped, astonished.

“Some words, yes.”

“Words only for the girls?”

“That’s right. You try it,” said Malee. “Sawat Dee Kha.”

Ariadne tried the syllables. They tumbled in her mouth like clouds.

The man pointed to the picture she had drawn. She’d been clutching it in her hands to show to her father. “What is this?” he said.

She held it up. “It’s a mermaid.”

“Ah,” he said, studying her lines. “It is Suvannamaccha.”

“Suva…?” began Ariadne.

“Suvannamaccha,” said the man. “She live in the ocean, half girl, half fish, like this…” he waved his hand through the air, making a fish.

“She’s a mermaid?”

“She is good luck.”

In the distance, her father appeared on the path. He wiped a hand across his forehead in the heat. He wore a suit though he had taken the jacket off and draped it over his arm. He waved with his other hand, and Ariadne broke away to scurry down the pathway towards him, flapping her drawing in the air, waving back to him.

By the time they had eaten, it was dark. It was quiet on the grounds except for the clicking of a gecko and the distant sound of the surf.

“Are you getting tired, Ariadne?” Her father held her hand and they walked slowly. She hung heavily on his hand.

“We have secret words,” she said. “Only for girls.”

“Only for girls?” he considered. “Then you shouldn’t tell me.”

“I won’t.”

“Are you getting tired?”

“No,” she said, though she dragged her feet as they walked.

They strode over the fairy tale bridge again. The little blue lights were already on around the trees and the old man, the one who’d said hello, was wrapping up a hose, finishing his day. He wore rubber boots now that came up almost to his knees. Ariadne stopped by the path and very solemnly pressed her hands together nodded. “I forget the words to say,” she said to him.

The old man grinned. He nodded at the father, a gap between his teeth. He pressed his own hands together and bowed deeply to the girl.

“Sawat Dee Khrap,” he said. “Are you going to see the mermaids?”

Ariadne’s eyes widened. “Are they here now?”

“We have a story,” said the man. “One of the gods tried to build a bridge, across the sea, but when he threw rocks in the water, to make the bridge, the mermaids stole the rocks.”

“A bridge?” said Ariadne.

Her father drew out a little notebook from his pocket.

“Don’t mind him,” said Ariadne. “He always writes things down. He collects stories.”

“Suvannamaccha,” said the old man. “She fall in love with the god and…”

“And they made the bridge?”

“Yes,” said the old man.

“Is that why she is lucky?” said Ariadne.

The old man coiled another loop in the hose. He hoisted it over his shoulder. He grinned and nodded again. “Yes.”

“My father says I shouldn’t believe in luck,” said Ariadne.

“No,” said the man. “But it is important that luck believes in you.

A swatch of gold still hung on the horizon though the beach was dark. The waves were light, gurgling up onto the sand as if they were sleepy. Far down the beach on the right, the lights of a distant village twinkled across the water.

“Why can’t I see the stars here daddy?”

“Oh,” he said. He held a hand over his brow, as if protecting his eyes from the sun and looked out across the almost black ocean. “It must be the humidity. It’ll cool later and become off.”

“What’s humility?”

“Humidity. Water, in the air.”

Ariadne pouted her lips. “That’s crazy,” she said. “How can there be water in the air and how come I can never see the stars?”

“They’re out there, honey.”

She shook her head. “Sometimes I don’t believe in stars anymore.”

“They’re out there, believe me.”

“Should we throw some rocks?”

“I suppose. Just don’t bonk any mermaids.”

“That’s not even funny, Daddy.”

Ariadne crouched down, scooping her hand through the sand like a rake, searching for a small rock. She came up with a piece of coral and looked at it in her hand for a moment. It looked like a bumpy white rock. She tossed it a few feet into the water and it sank with a tiny plunk.

“Did you see that?” she said.

“Very nice, Ariadne.”

“No, Daddy, look. Did you see it?” She kicked off her sandals and trotted to the water’s edge.

“Ariadne!” Her father clucked his tongue. He stood still for a moment then kicked off his own shoes and rolled up his pant legs. “Wait,” he said. And he waded in after her, stopping when the water was just above his ankles. Ariadne was staring at something in the water. The waves were gentle, almost non-existent, just lapping around her calves.

“Look,” she said. She knelt down and poked a hand into the water. A streamer of flickering lights traced behind her hand.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” said her father. “That’s phosphorescence.”

Ariadne kicked at the water and a splash of sparkles burst in front of her. “Look,” she said, “I’m making stars.”